Lattices and Confusion Networks for Automatic Speech Recognition

Interest in speech recognition has been steadily increasing as the presence of speech enabled devices continues to proliferate the market. Lattices and confusion networks have proven to be a useful topology for representing competing automatic speech recognition (ASR) predictions in a number of settings. These include machine translation [1], confidence score estimation [2], and deletion prediction [3]. In this post, I'll present lattices and confusion networks, and discuss why they are useful in ASR.

Automatic Speech Recognition

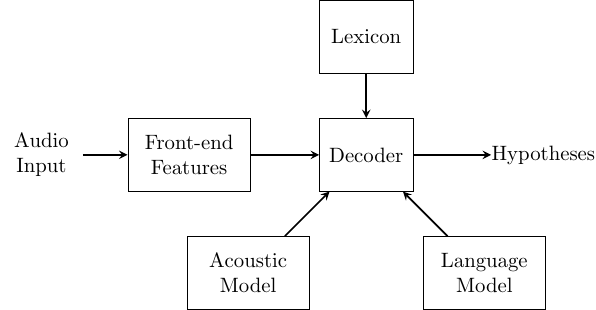

Before jumping into the thick of things, let's have a high-level look at the components making up an ASR system.

An audio recording is passed through the acoustic front-end stage which extracts features such as Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) from the raw audio samples. A decoder determines the most likely sequence of words given the observed utterance, described by the feature vector. In order to determine the search space, the decoder requires an acoustic model, language model, and lexicon. The acoustic model assesses the likelihood of the acoustic sequence while the language model indicates the joint probability a particular word sequence. Since it is common for an acoustic model to operate on a sub-word level, a lexicon is required to map the sub-word level acoustic sequence to a word level acoustic sequence. Collectively, these components tackle the problem of ASR through an application of Bayes' decision rule as defined by

where the acoustic utterance is described by  and the word sequence is defined by

and the word sequence is defined by  [4]. The conditional likelihood of an acoustic utterance given a word sequence,

[4]. The conditional likelihood of an acoustic utterance given a word sequence, ) , is determined by the acoustic model while the language model defines the joint word probability of the word sequence

, is determined by the acoustic model while the language model defines the joint word probability of the word sequence ) . The decoder is responsible for executing the

. The decoder is responsible for executing the  operation which entails searching for the most likely transcription.

operation which entails searching for the most likely transcription.

One-best sequences: A simple way to represent transcriptions

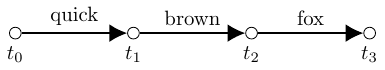

A straightforward implementation of the decoding process produces a sequence of words corresponding to the most probable transcription according to the maximum likelihood estimate. This single hypothesis for the audio transcription is called the one-best sequence. This is what you see on your screen when using Siri and many other voice activated systems. The one-best sequence can be represented graphically as shown below. In this illustration, each word is associated with an arc between nodes. The time stamp between each word is contained by the nodes themselves. This format is not a strict requirement of one-best sequences. We could associate the start time of each word and the word itself with the nodes in the one-best sequence.

The problem with one-best sequences is that many speech and natural language processing applications may benefit from the information contained in the alternative hypotheses. In order to take advantage of these competing transcriptions, we would like to represent them in a form which is memory efficient and conducive to the application of machine learning. To this end, the lattice topology is introduced.

Lattices for representing competing hypotheses

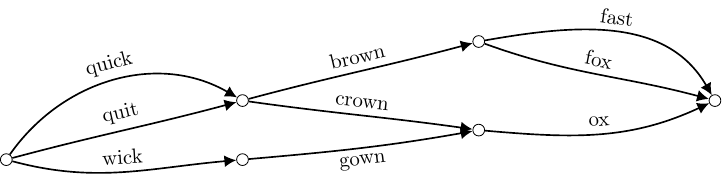

A set of N alternative transcriptions, or N-best hypotheses, can be efficiently represented in a graphical structure called a lattice. Each path through the lattice corresponds with a predicted transcription for the given audio recording. The hypotheses which make up the N-best list are determined by ranking each transcription, using the maximum likelihood estimate, and selecting the N most likely word sequences. In the context of ASR, a lattice is a Directed Asyclic Graph (DAG) which enforces a forward information flow through time as shown below [5].

It is clear from this example that commonalities between different hypotheses can share the same nodes and edges in a lattice, thereby reducing the footprint of the N-best list. As was the case for the one-best sequences described above, words can be associated with the nodes or the arcs in the lattice. Furthermore, lattices are not simply restricted to the word and the time stamp information. Several word and sub-word level features can be embedded into this framework as long as they can be represented as a fixed-length tensor or vector.

Confusion networks

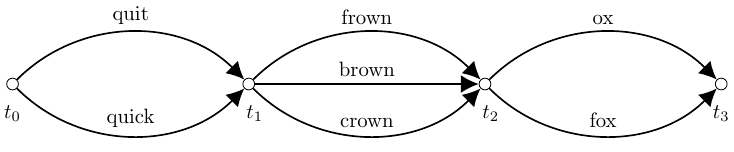

Confusion networks, also referred to as consensus networks, are an alternative topology for representing a lattice where the lattice has been transformed into a linear graph. This means that each path through the confusion network passes through all nodes in the graph. The process used to generate a confusion network from a lattice is a two stage clustering procedure which groups individual word hypotheses into time-synchronous slots. Each slot describes a set of competing word hypotheses over a single period in time [6]. This results in confusion networks having a sausage-like structure as seen in the example below.

One possible advantage of confusion networks over lattices is the ability to discard unlikely paths, thereby reducing the memory and computational cost of the competing hypotheses. Hence, we can think of confusion networks as a type of pruned lattice. In the context of deep learning for speech and natural language processing, confusion networks could provide an efficient mechanism for reducing some of the computational challenges associated with large lattices without degrading model performance.

References

- F. Stahlberg, A. de Gispert, E. Hasler and B. Byrne, “Neural machine translation by minimising the Bayes-risk with respect to syntactic translation lattices”, arXiv preprint arXiv:1612.03791, 2016

- Q. Li, P. Ness, A. Ragni, and M. Gales, “Bi-directional lattice recurrent neural networks for confidence estimation,” in ICASSP 2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2019, pp. 6755–6759.

- A. Ragni, Q. Li, M. J. Gales, and Y. Wang, “Confidence estimation and deletion prediction using bidirectional recurrent neural networks,” in2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT). IEEE, 2018, pp. 204–211.

- F. Wessel, R. Schluter, K. Macherey, and H. Ney, “Confidence measures for large vocabulary continuous speech recognition,”IEEE Transactions on Speech and Audio Processing, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 288–298, March 2001

- S. Young, G. Evermann, M. Gales, T. Hain, D. Kershaw, X. Liu, G. Moore, J. Odell,D. Ollason, D. Poveyet al., “The htk book,”Cambridge university engineering department, vol. 3, p. 175, 2002.

- L. Mangu, E. Brill, and A. Stolcke, “Finding consensus among words: Lattice-based word error minimization,” in Sixth European Conference on Speech Communicationand Technology, 1999.